Countering car blindness – what makes a prosperous city?

Why can’t we stop driving? Is it that we’re not worried enough about dying prematurely, don’t believe in climate change, or don’t care about the coming generations?

Whatever the reasons, the car has become symbolic of a wider malaise – a refusal to change course, even when faced with overwhelming scientific evidence of the car’s negative impact on our health and the health of the planet. We have all succumbed to “car blindness”.

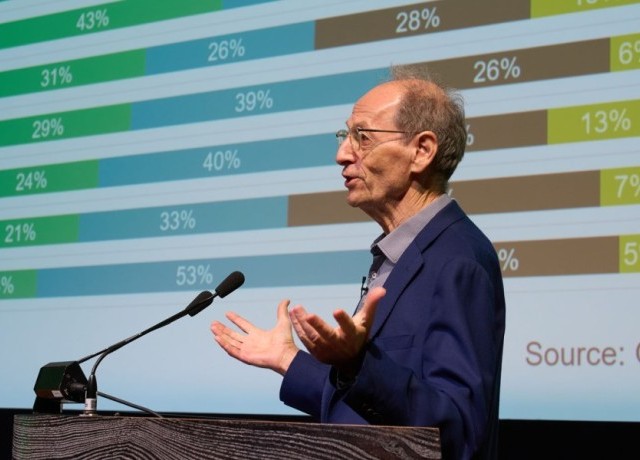

This was the context through which Professor Henrietta L. Moore, founder and director of the Institute for Global Prosperity, and chair in culture philosophy and design at University College London, framed her keynote talk at Healthy City Design 2025. If we are to counter car blindness and unshackle ourselves from our perceived dependence on what Moore calls the car industrial complex – i.e. the network of business, money, value chains and services that surround the car – then we need to reconceive our notion of what makes a prosperous city.

Of course, there are benefits to the car – it would not be “the most successful consumer product ever made” if it did not, and the sense of freedom, convenience and autonomy it provides tugs at us in an emotional as well as practical way. But commuting by car also makes us miserable. By illustration, Moore pointed to an international survey from 2019, where those lucky enough to cycle and walk to work reported the greatest levels of happiness. “Traffic has slowed car speeds in cities like London to around 8 mph,” she said, “at which point you might as well amble about with a cart and horse.”

“Prosperity is often too narrowly defined as income and jobs,” Moore reasoned, but transport reform is key to “any enlarged vision of the good life we might want to espouse”.

Social infrastructures and social solidarity

We could learn much from the experience of Bogotá, the capital of Colombia, and the policies of its former mayor, Enrique Penalosa, who built hundreds of parks, bike tracks, bus lanes and sidewalks during his time in office. “These were linked to libraries, hospitals, schools, nurseries, and water and electricity systems,” Moore noted, “enhancing not just connectivity but social infrastructures and social solidarity. For Penalosa, a protected bus lane didn’t just keep cyclists safe; it was a symbol that showed that a citizen riding a £50 bike is equally important as one driving a £50,000 car. A bus stuck in traffic represents not just inefficiency but inequality.”

Yet in many cities around the world, public transport is a poor relation, with bus and train services a common disgruntlement of citizens “from Johannesburg and Reykjavik to Lagos and Manila”. Public transport is vital in places where a majority of people still do not drive, said Moore, who again referenced Penalosa: “An advanced city is not one where the poor own a car but one where the rich use public transport.”

Nevertheless, cars continue to dominate our built environment – not just when in motion, which is only around 4 per cent of the time but also when parked, for the remaining 96 per cent of the time.

“The car’s insatiable need for space is reflected in almost every city in the world,” lamented Moore. “In London, 14,000 sq km of its land goes just to parking, and that’s about the size of ten Hyde Parks. In Barcelona, Spain, cars account for just 20 per cent of journeys in the city but occupy 60 per cent of the city’s space. In the United States, there is more space for parking cars than there is housing for people.”

Its relationship with housing is also damaging to prosperity, according to Moore. “Housing is often still sold with off-street parking attached, which actually inflates the price of the housing,” she said. “It would be fair to say that bundling parking with housing creates free homes for cars and more expensive homes for people.”

She pointed out that one off-street parking space consumes between 25 and 33 sq m – roughly equivalent to the average living space per person in China, Spain and South Korea, and even larger than the average space in India, Brazil, Mexico and Poland.

Human health issues linked to the generation of air pollution from road vehicles are also vast – in volume and variety. Ambient air pollution accounts for about 4.2 million deaths every year globally. Yet, there are perhaps even more sinister repercussions, with research revealing a worrying association between continual exposure to particulate matter and reduced sperm health. “This aligns with an alarming fertility crisis,” Moore reasoned, “where men’s sperm count in heavily polluted cities around the world has dropped by almost 60 per cent since the 1970s. And that would make men in those situations today about half as fertile as their grandfathers. One child in every classroom in the UK is now born by IVF. And air pollution costs the UK economy £27bn annually.”

Traffic has slowed car speeds in cities like London to around 8 mph, at which point you might as well amble about with a cart and horse

Going Dutch

Public unease with the dominance of the car is not new. One of the earliest campaigns against cars taking over towns began in the 1960s, in the Netherlands, and it manifested into the development of “woonerf”, or liveable streets. These small-scale, neighbourhood-led developments, pioneered in the city of Delft, were a response to a rise in child traffic fatalities and included speed control measures, such as speed bumps and chicanes, which are commonplace today. “These control measures were integrated into Dutch traffic code in 1976, expanding then across Europe,” Moore explained. “And the issue was non-politicised because everyone could agree on the fact that they didn’t want to see any more children injured by a car.”

Dutch cities continue to innovate. In Rotterdam, there are now sensors that give priority to cyclists at intersections when it rains. Other interventions include wind-protected corridors and photovoltaic surfaces, which generate power as well as providing cycling surfaces. “The secret to success is taking a whole-system approach to innovation,” Moore mused, “placing connectivity at the core of new design, linking housing to mobility and both to new job opportunities. A socially connected city is a healthy city.”

Reforming mobility, she added, can help bring us together around broader changes we would like to see at a societal level, and cut through the division that threatens our freedom and future prosperity. Said Moore: “As we face the climate crisis, we should be building new institutions and new practices that deliver the freedoms that matter to us in a changing world. So, when division threatens and when choices involve trade-offs, we can start by taking account of others’ perspectives. This requires us to build cities that encourage us to interact with each other, and urban infrastructures that provide for the diverse and changing needs of different communities in times of uncertainty.”

While the car came to be seen as a symbol of individual freedom in the 20th century, we now need to be able to believe in new shared freedoms for the 21st century.

But what are these freedoms? For Moore, they include “the freedom to send your kids to the shops on their own like those living in Superblocks in Barcelona can. Somewhere to rest and enjoy greenery away from the noise of city traffic, as seen by the dismantling of a busy highway in Seoul to restore a medieval stream basin. Or the freedom from rising heat and unpredictable weather, where the impermeable shell of road surfacing can be replaced by flood-absorbent paving, shrubbery and tree cover, as in Karachi.”

If solutions are to be found to improve liveability in cities and for the planet, then several intersecting challenges have to be addressed simultaneously. And the car, Moore argues, is at the core of most of them.

Presenters

Co-authors

Event news

Delivering a sports-led regeneration with major brand pulling power

27th October 2025

Housing and health – where building blocks for a good life are created

27th October 2025

From a ‘Dirty Old Town’ to a thriving, modern city

27th October 2025

Actions to improve urban renewal and health equity

2nd September 2024