Embedding transformation in healthcare capital programmes: Lessons from leading approaches

This paper will explore approaches to embedding transformation within capital programmes, addressing how programme leaders approach clinical and digital transformation; collaborate with the hospital and wider health and care ecosystem; share best practice and knowledge; and manage risks associated with hospitals that are too small or not sufficiently ambitious.

Abstract

Healthcare systems worldwide are under increasing pressure to meet the demands of ageing populations with growing health needs, ageing estate and rising costs. Providing new bedded capacity and replacing inadequate estate are only part of the solution. Examples from new estates opening at the Royal Liverpool University Hospital (UK), Midland Metropolitan University Hospital (UK, main image above), and the Royal Adelaide Hospital (Australia) highlight the significant operational and financial challenges faced by new developments where transformation assumptions in and out of hospital are not delivered.

Equally, the UK’s New Hospital Programme (NHP) has needed to set ambitious transformation objectives to demonstrate a return on investment – expecting digital and clinical transformation to support a 12-per-cent reduction in length of stay and a 1.8-per-cent reduction in demand for acute care. This is in the face of annual increases in demand for non-elective services from an ageing population. Therefore, it’s critical that healthcare transformation, in and out of acute facilities, occurs alongside building planning and design, as re-providing acute estate is no longer viable in isolation. Every new capital programme needs to plan and design for both transformation in design and clinical practice.

This research paper will explore approaches to embedding transformation within capital programmes. It will address how programme leaders approach clinical and digital transformation; collaborate with hospital and the wider health and care ecosystem; share best practice and knowledge; and manage risks associated with hospitals that are too small or not sufficiently ambitious. The paper will make use of primary research with programme directors for new hospital builds in the planning stage, as well as recent openings. Methods will include interviews with, and surveys featuring, qualitative and quantitative questions. Data will be analysed using qualitative and quantitative techniques. Programme directors will be reached through our national network, with the results of the primary research presented at Congress. Key themes from the research will be summarised and presented, providing valuable insights into the approaches undertaken by various projects.

From initial conversations with our clients and network, we know that there are significant differences in how well-prepared organisations are for change. The risk of wasting the investment opportunity or not planning for transformation early could have significant impacts on patient care for years to come. We expect our research to shed light on the approaches undertaken by projects, identifying best practice and steps to better embed transformation in building planning and design of healthcare capital programmes.

Introduction

Global pressures from ageing populations, rising demand, and escalating costs require a fundamental shift in healthcare infrastructure planning. Traditional ‘replace and build’ is inadequate; large-scale capital programmes require integrating physical infrastructure with deep clinical, digital, and cultural change.

A gap persists in understanding how to embed effectively deep transformation within complex healthcare capital programmes, often focusing too narrowly on “bricks and mortar”. Therefore, this paper seeks to answer the question: How can clinical and digital transformation be effectively embedded within large-scale healthcare capital programmes, and what practical strategies can programme leaders adopt to ensure its successful delivery and operationalisation?

Our research bridges this via an exploratory qualitative study, synthesising key concepts in the literature, analysis of recent hospital openings, and New Hospital Programme (NHP) director interviews and perspectives.

Background: Context of the New Hospital Programme in UK

New Hospital Programme

The NHP, formally established in October 2020, commits to building 40 new hospitals by 2030, consolidating 32 newly announced schemes with eight pre-existing projects. In May 2023, an additional seven hospitals, primarily constructed from reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete (RAAC), were added owing to safety risks. In January 2025, funding and construction timelines were confirmed under the Labour Government, with 16 builds due to start construction before 2030.

To overcome the historical issues of individual hospital builds often leading to budget overruns and delays, the NHP is adopting a centralised, programmatic approach known as ‘Hospital 2.0’. This initiative aims to define and implement standardised designs, capitalise on economies of scale, improve productivity, and ensure value for money across the programme. Hospital 2.0 incorporates sustainable and modern methods of construction (MMC), designed for manufacturing assembly, and fosters long-term certainty for the construction industry. Work is currently underway to define these standards and implement them through Wave 1 schemes, with future waves expected to follow suit.

Financial challenge of new builds within NHS funding context

While the NHP represents a significant national capital investment in modernising the NHS estate, its delivery simultaneously introduces a substantial and often underestimated financial challenge to individual NHS trusts in the form of increased revenue costs. Upon completion of a new facility, trusts incur recurrent increases from two key charges:

- Additional operational costs: potential increases in workforce costs from single room layouts, additional facilities management costs (e.g., heating/cleaning) from larger floor plans, higher digital operating from maintaining more systems.

- Depreciation: A non-cash accounting charge reflecting the asset’s consumed economic value, impacting financial performance by reducing surpluses or exacerbating deficits.

- Public Dividend Capital (PDC) charges: A direct cash charge paid to the Department of Health and Social Care on the value of public capital invested in the trust’s assets.

In the current severe NHS financial climate, where additional revenue funding is severely limited and trusts face significant existing pressures, these new charges pose an immense burden. Trusts are compelled to identify substantial and recurrent savings from their existing budgets to offset these costs.

This revenue funding challenge falls squarely on individual trusts and their integrated care systems, as the NHP’s primary focus remains on managing the capital cost. This creates a critical potential funding gap that trusts must bridge, making the financial sustainability of new builds highly dependent on locally driven operational transformation and productivity improvements.

Transformation requirements

The financial pressures outlined above mean that NHS trusts cannot simply replace like-for-like when building new hospitals, since they are mandated to achieve substantial efficiency savings.

The substantial financial commitment of new hospital builds, coupled with the NHP’s ‘Hospital 2.0’ vision, necessitates profound clinical, digital, and cultural transformation. This involves fundamentally reconfiguring care pathways, moving services from acute hospital settings into community and primary care, and adopting new technologies. It means achieving more with less, improving efficiency, productivity, and patient outcomes within existing and often reduced bed bases.

A core assumption underpinning these transformations is the significant shift of care out of the hospital and into community settings. This long-standing NHS policy aims to alleviate acute hospital pressure, address rising demand, and deliver patient-centred care closer to home. It involves services such as minor urgent care, diagnostics, and chronic disease management moving to primary care, local clinics, or patients’ homes.

While offering benefits like improved patient experience and reduced hospital admissions, this strategy presents significant challenges owing to trusts’ limited direct control over broader community infrastructure, historical underinvestment in community services, persistent workforce shortages, and funding imbalances. This reliance on external system partners introduces significant risk, as the successful operationalisation and financial sustainability of new hospitals heavily depend on a transformed wider health and social care system outside a trust’s immediate purview.

Therefore, to navigate these complexities and ensure new facilities deliver intended benefits, NHP schemes must focus relentlessly on robust internal clinical and digital transformation, moving beyond new structures to concentrate on fundamental changes within the hospital’s operations, pathways and technology, ensuring the infrastructure truly enables modern, efficient care.

Understanding transformation in healthcare capital programmes: Literature review and key concepts

New hospital builds and major capital programmes are fundamentally about transforming healthcare delivery, not just constructing buildings. While the physical infrastructure provides the platform, success hinges on enabling profound shifts in clinical models, digital capabilities, and organisational culture. This section explores key concepts from relevant literature to frame our understanding of transformation within this context. Drawing insights from across sectors, we examine frameworks essential for strategic planning and successful execution.

NHP schemes must focus relentlessly on robust internal clinical and digital transformation, moving beyond new structures to concentrate on fundamental changes within the hospital’s operations, pathways and technology, ensuring the infrastructure truly enables modern, efficient care.

The Cost of Quality: Preventing failure in new hospital builds

The Cost of Quality (CoQ) framework, adapted from manufacturing, is crucial for assessing how investments (or lack thereof) in preventing errors impact overall project costs and outcomes. It categorises costs into:

- prevention costs: Investments made to prevent quality issues (e.g., upfront planning, robust design, training, system integration, adequate risk assessment);

- appraisal costs: Costs associated with evaluating quality (e.g., inspections, audits, testing);

- internal failure costs: Costs incurred when defects are found before delivery to the customer (e.g., rework, scrap, delays); and

- external failure costs: Costs incurred when defects are found after delivery to the customer (e.g., warranty claims, recalls, customer dissatisfaction, reputational damage, long-term operational inefficiency).

In healthcare, external failure costs manifest as compromised patient safety, staff burnout, prolonged operational inefficiency, and significant unforeseen financial burdens resulting from unaddressed upstream issues. Effective investment in prevention costs is paramount to minimise these downstream failures.

Ensuring success: Programme management, benefits realisation, and assurance

Successfully embedding transformation in NHP schemes requires robust, proven methodologies. Three critical frameworks provide the necessary discipline and focus:

- Managing successful programmes (MSP): This provides the structured governance and management framework to navigate the inherent complexity of transforming healthcare delivery alongside building new facilities. It ensures effective stakeholder management, risk control, and alignment across diverse workstreams.

- Benefits realisation management (BRM): Crucial for NHP projects, BRM shifts the focus from simply completing a build to ensuring the programme delivers its intended outcomes and value. It mandates a structured lifecycle for identifying, planning, tracking, and sustaining the benefits (e.g., reduced length of stay, increased patient satisfaction, cost savings) that the new facility is designed to enable.

- Project assessment frameworks (PAF): Incorporating independent scrutiny, such as gateway reviews, PAFs provide objective oversight at key decision points. For NHP schemes, robust PAFs promote transparency and help identify risks early, ensuring continuous external validation that programmes are on track to deliver their transformative objectives.

Collectively, these frameworks act as the backbone for NHP schemes, ensuring that the ambitious transformation goals are not just envisioned but systematically planned, managed, and delivered.

The human element: Driving change through behavioural science

Even the most meticulously designed new hospital or perfectly planned digital system will fail if the people using them aren’t engaged and supported. This is where behavioural science becomes indispensable. Mandating change is rarely sufficient; genuine and sustainable transformation requires understanding human decision-making and motivation.

For NHP schemes, integrating behavioural science means:

- Engaging staff: Fostering understanding and excitement about new ways of working.

- Building commitment: Ensuring ownership through active participation in redesign processes.

- Targeted training: Providing the necessary skills and confidence for new roles and technologies.

- Addressing resistance: Proactively identifying and mitigating cognitive biases or ingrained habits that could hinder adoption.

Investing in these people-centric strategies acts as a vital prevention cost against human-related failure costs, ensuring that the vast investment in new buildings translates into successfully adopted new models of care by the NHS workforce.

From plans to practice: Successful operationalisation

Effective operationalisation is the true measure of a new hospital’s success. It requires a deep understanding of interdependencies, from patient flow to clinical pathways and technology. The NHP vision relies on achieving specific patient benefits, such as reduced lengths of stay and improved access, which are only realised through successful new models of care. This demands seamless integration across clinical, digital, and workforce elements, ensuring that the new physical infrastructure genuinely enables transformative changes in care delivery and patient outcomes.

Research methodology

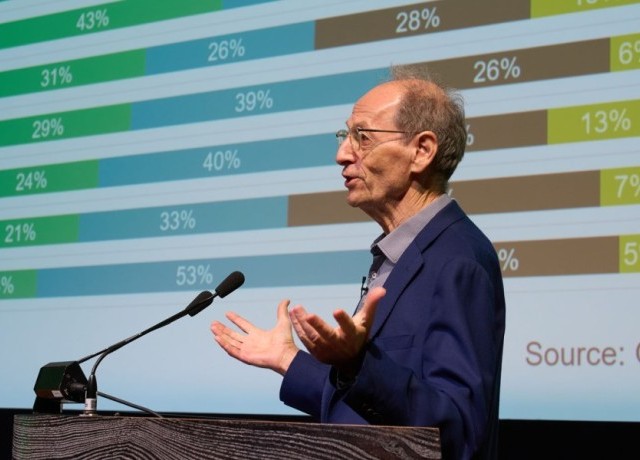

This exploratory qualitative study utilised semi-structured interviews to investigate programme leaders’ approaches to embedding transformation in UK healthcare capital programmes. This design enabled nuanced understanding of complex processes and diverse stakeholder perspectives. Participants included programme directors, executive sponsors, and network contacts leading significant healthcare capital programmes, primarily NHP Wave 1 Trusts. Eight interviews were conducted, purposively sampled based on direct project involvement.

Data were collected through semi-structured interviews, guided by open-ended questions exploring service transformation’s role; specific transformation plans; governance, skills, and methodologies; work with system partners; and improvement areas. Interview data underwent thematic analysis. Insights were then applied to illuminate experiences of the Royal Adelaide Hospital, the Royal Liverpool University Hospital, and Midland Metropolitan University Hospital, interpreting case studies through established frameworks (e.g., Cost of Quality (CoQ)) to demonstrate how strategic choices impacted project success and operational outcomes.

A post-interview survey self-assessing programmes against five areas was used: quantification of transformation gap; visibility of risks; system alignment on required changes; transformation trajectories; and tracking and monitoring of change.

Findings: Approaches to embedding transformation

This section presents key findings on approaches to embedding transformation in healthcare capital programmes, drawing on insights from interviews with programme leaders and illustrative case studies. It highlights critical enablers, persistent challenges, and the essential considerations for achieving successful and sustainable transformation. Recent case studies, examined through the CoQ lens, highlight key lessons and pitfalls.

Headline findings

The analysis reveals several critical headline findings regarding transformation in new hospital programmes.

- New Hospital Programme builds assume significant transformation across clinical practice, digital, and out-of-hospital care (outside of acute provider control) as part of their business cases and sizing of bed requirements.

While there is an awareness of the risks associated with these complex schemes, case studies showed there is often insufficient upfront investment – in terms of both strategic foresight (headspace and capacity) and tangible resources – to adequately mitigate these risks. - Despite these systemic challenges, trusts are acutely aware of the scale of the transformation required for their new builds – and that these risks sit with the trust and integrated care boards, not necessarily the national NHP programme.

- Encouragingly, common themes are emerging that define what good preparedness and planning for transformation looks like, such as the alignment of clinical improvement plans (CIPs) and commissioner plans in the medium term.

- Significant challenges persist, particularly concerning capacity, resourcing, capability, and delivery track record. There is often a lack of honesty about the scale of whole system change required to meet planning assumptions, and readiness for delivery of complex transformation.

- Further work is needed, within individual schemes and at programme level, to fully integrate clinical transformation, align with wider initiatives, and prioritise delivery from 3-5 years pre-opening.

Key themes for successful transformation

- Proactive, internally driven transformation: New hospitals necessitate fundamental reshaping of care delivery to enable new models of care, driving assumed efficiencies. Transformation must be internally led, fostering genuine ownership and active participation from clinicians and operational staff, with the acute trust often serving as the pivotal local focal point for system-wide change.

- Comprehensive target operating models (TOMs): Detailed TOMs integrating clinical pathways, digital workflows, workforce planning, and data define the future state. These must be clinically led, focusing on every patient pathway step for practicality and frontline staff buy-in.

- Robust management and governance for benefits realisation: Disciplined MSP application is essential for managing benefits trajectories ahead of moving into a new hospital. Effective benefits realisation is underpinned by robust governance, including structured programme offices, active trust board involvement, and non-executive directors (NEDs) driving independent assurance through gateway reviews. Programme management offices (PMOs) are instrumental in holding teams accountable for benefit driver metrics and managing risks.

- Strategic digital integration: Digital transformation fundamentally enables new care models. Implementing major digital systems like EPR ahead of the physical build (Midland Met) acts as a “test case” for model changes, mitigating risks by separating major system go-lives from facility openings.

- Early and strategic investment in transformation ahead of opening: Leaders stressed substantial upfront investment in transforming service models, often through dedicated transformation teams. Proactively funding “double running” roles during transition is crucial for concurrent operations, training, and gradual embedding of transformations without compromising existing service delivery, aligning with CoQ prevention costs.

- People-centric change management and adaptability: Successful transformation hinges on workforce adoption of new care models, requiring proactive, people-centric strategies. Approaches that avoid overloading teams and build internal capability are vital. Iterative approaches, such as testing concepts in “concept wards,” allow for real-world feedback and incremental embedding of behavioural change.

- System-wide collaboration: New Hospital Programme schemes are inherently intertwined with the wider health and social care ecosystem. Success hinges on deep, intentional collaboration across providers, commissioners, and national bodies. An acute trust relies on wider system changes to achieve its transformation goals. Practical tools, such as a system assumption log across models and change programmes, can be helpful in understanding interdependencies and changes that require controlling.

Challenges and readiness issues

Interviewees identified significant challenges impeding readiness and risking programme success:

- Underestimation of transformation scale and financial implications: The sheer scale of required service model transformation is frequently underestimated, leading to “heroic assumptions” in business cases. “Like-for-like” replacement is financially and operationally unviable owing to prevailing economic and workforce constraints.

- Difficulty in quantifying and realising benefits: Trusts struggle to quantify specific interventions and establish a clear “bridge” to the transformed state. This hinders progress tracking, buy-in, and the delivery of pre-opening changes.

- Lack of internal capability and resources for transformation: Trusts face significant challenges in building sufficient internal capability and capacity for change, particularly within reactive environments. Securing dedicated clinician time amid operational demands and obtaining upfront funding for “double running” roles – crucial for transition – remain persistent challenges.

- Fragmentation and lack of holistic oversight: Achieving a holistic view of all transformation activities remains difficult. Interviewees observed a lack of joined-up thinking and limited best practice sharing across the NHP, often leaving trusts feeling isolated.

- System-wide co-ordination gaps: Co-ordinating transformation across the wider health and social care ecosystem proves challenging. A perceived “lack of vision” and “unwillingness among some stakeholders to confront the significant challenge” risk stagnation if transformation efforts do not keep pace.

- NHP’s focus and clarity: Concerns exist regarding a perceived “gap in NHP’s understanding of revenue implications and transformation practicalities,” for example, on the topic of single rooms. Clarity on NHP decision-making authority and timeframes was also a concern. It’s understood that local transformation risks (operational and financial) ultimately sit with trusts and local systems, rather than the national teams.

NHP programmes’ readiness for change

Our post-interview survey results showed:

- 75 per cent of programmes neither agreed nor disagreed that programmes or health and care systems understood the changes needed to deliver business case assumptions.

- 50 per cent agreed that the programmes have captured the risks.

- 50 per cent agreed the wider system and programme were aligned on changes

- 75 per cent had not developed transformation trajectories required from present day to opening, allocating these to change projects.

- No programmes tracked transformation against improvement trajectories required to deliver the change.

It was noted that further work is needed on programmes at Outline Business Case stage to understand this change more fully, and not all programmes were at this stage yet. One programme said they understood the need for a comprehensive transformation strategy and implementation plan and are in the process of developing this.

Illustrative cases: Cost of Quality in practice

This next section delves into three illustrative case studies, providing practical insights into the challenges and successes of embedding transformation in healthcare capital programmes. The information presented here is derived from publicly available reports and news articles.

The new Royal Adelaide Hospital, Australia (Credit: Sandyx99; CC licence, Wikipedia)

The new Royal Adelaide Hospital, Australia (Credit: Sandyx99; CC licence, Wikipedia)

Royal Adelaide Hospital Case Study: High external failure costs from prevention gaps

The Royal Adelaide Hospital (RAH), which opened in September 2017, was envisioned as a state-of-the-art public-private partnership (PPP) facility and the largest capital investment in South Australian history. Despite ambitious goals, its journey was marked by massive cost overruns and chronic delays. The RAH’s experience provides crucial insights into major infrastructure development pitfalls.

The hospital’s design implicitly assumed seamless integration of its advanced physical infrastructure with efficient workflows, a prepared workforce, and robust IT systems for high-quality, cost-effective care. However, immediately post-opening, the RAH experienced significant operational and financial distress.

Key challenges and systemic pressures included:

- Operational dysfunction: Chronic emergency department overcrowding, inefficient patient flow (extended lengths of stay), and critical IT system unpreparedness (EPAS) severely undermined efficiency.

- Workforce crisis and morale: Severe staffing shortages, high burnout, and declining morale emerged due to excessive workloads.

- Financial challenges: Facing budget overruns of more than $600 million over five years, the Central Adelaide Local Health Network (which includes the RAH) was put into administration, with a private firm brought in during 2018 to manage its finances and operations.

- Clinical governance issues: Weaknesses were linked to serious incidents, such as medication errors.

These challenges correlate with gaps in upfront “prevention” activities. Critical oversights included insufficient upfront investment in systemic change, unrealised business case assumptions, and inadequate pre-opening planning for PPP complexities, IT readiness, and design impacts on workforce. This led to struggles with capacity and operational readiness from day one, with the RAH exposing existing health network strains.

These unmitigated “prevention costs” led to substantial “external failure costs”. Operational and financial distress, the need for external financial administration, compromised quality/safety, and severe workforce issues represent a clear financial and human resource drain. These consequences impacted patient care and financial stability, taking considerable time to rectify.

While the RAH has since undertaken significant work to address these challenges, its journey serves as a crucial lesson in the substantial time, effort, reputational damage, and significant financial risk to the entire health system that can result when complex interdependencies of infrastructure, transformation, and operational readiness are not fully anticipated.

It's important to acknowledge that the Royal Adelaide Hospital has since undertaken significant work to address these deep-seated challenges, including efforts to optimise its digital systems, re-engage staff, and strengthen clinical governance.

Royal Liverpool University Hospital, UK (Credit: Rodhullandemu, CC licence Wikipedia)

Royal Liverpool University Hospital, UK (Credit: Rodhullandemu, CC licence Wikipedia)

Royal Liverpool University Hospital Case Study:

The Royal Liverpool University Hospital (RLUH), which opened in October 2022, was conceived as a state-of-the-art facility despite a protracted, costly development due to contractor collapse. While the new hospital is a significant investment with successful clinical innovations, such as virtual wards, improving patient experience, its journey nevertheless highlights critical lessons.

The RLUH’s design assumed significant transformation towards decentralised care, including reablement and virtual wards, to optimise bed utilisation and improve patient outcomes. However, immediately post-opening, the hospital faced acute operational challenges. Key challenges and systemic pressures included:

- Emergency department (ED) overcrowding and flow: Persistent patient flow issues led to severe ED overcrowding and reliance on "corridor care.”

- Staff morale: Medics cited “dreadful conditions” and declining care due to operational chaos.

- Bed capacity impact: A smaller acute bed base (640 new versus 685 old) exacerbated pressures from insufficient social and community care capacity.

These challenges correlate with gaps in upfront “prevention” activities, such as miscalculating future demand, insufficient community capacity assessment, and inadequate contingency planning.

Despite awareness of national patient flow issues, moving to a smaller acute bed base without fully assuring wider social and community care capacity created significant operational difficulties. A lack of robust system-level demand modelling, integrated out-of-hospital care pathways, and contingency plans for external constraints rendered the hospital vulnerable from day one.

These unmitigated “prevention costs” notably contributed to substantial “external failure costs”. ED overcrowding, prolonged patient waits, and impacts on staff wellbeing had clear implications for patient safety and efficiency. The ongoing need for crisis management imposed considerable, unforeseen financial and human resource burdens, taking years to rectify.

While the RLUH’s emergency department has since been rated ‘Good’ by the CQC, its journey serves as a crucial lesson in the substantial time, effort, and potential reputational damage that can result when transformation complexities are not fully anticipated and mitigated.

Midland Metropolitan University Hospital, UK

Midland Metropolitan University Hospital, UK

Midland Metropolitan University Hospital Case Study: Demonstrating effective prevention strategies

The Midland Metropolitan University Hospital (MMUH), which opened in October 2024, was conceived as a “super hospital” consolidating acute and emergency services to drive integrated, community-focused care. The MMUH’s initial operational outcomes have been largely positive, demonstrating the potential of its new care pathways.

Its design assumed a net reduction in acute bed capacity offset by heavy reliance on innovative community-based care pathways (SDEC, virtual wards) to prevent admissions and facilitate discharges, transforming acute care within a wider integrated system.

The MMUH has shown promising initial operational outcomes within its first 110 days, including improvements in emergency department performance, ambulance turnaround times, and reduced medical admissions. Its long-term success is subject to ongoing systemic factors, including continued investment in its workforce and ongoing support for staff adaptation to new technologies and operational models.

The MMUH’s approach exemplifies the critical need for system-wide understanding of the transformation gap to new hospital size through its system-wide programme “More than a hospital”. Its success hinges on a robust system-level business case to shift resources and finance into the community, honestly assessing true costs. Its proactive management reflects robust grip on impact and change trajectories, delivering transformation up to opening, underpinned by implicit de-prioritisation focusing the organisation on change.

The MMUH’s early journey underscores that ambitious healthcare transformation extends beyond the physical build, requiring sustained viability of its entire care ecosystem. This case is a crucial lesson in the substantial commitment required to build infrastructure and perpetually secure integrated community services essential for long-term operational success and system financial health.

Discussion: Synthesising learnings and charting a route for transformation

Our research firmly establishes that new hospital builds are profound, multifaceted transformations of healthcare delivery, extending far beyond mere construction projects. The evidence from our findings and illustrative case studies – particularly the well-documented operational and financial challenges faced by the Royal Adelaide and Royal Liverpool hospitals post-opening – powerfully demonstrates that the challenge of embedding comprehensive transformation is very real, and it can have profound, long-lasting implications for NHS trusts, even if almost every other aspect of the capital build goes precisely to plan. Failing to effectively integrate deep clinical, digital, and cultural change with the new physical infrastructure can lead to significant operational challenge and severe financial distress upon activation.

While our interviews confirm that individual trusts generally possess a high-level of understanding of the inherent risks associated with such radical transformation, we found a concerning collective tendency to inadvertently underestimate the true scale and complexity of this challenge, often struggling to fully grasp the profound extent of the risks involved. This underestimation is particularly worrying for individual trusts striving to meet their objectives, but also for entire regions, especially in areas where multiple NHP schemes are progressing simultaneously. Such concentrated activity could create compounding pressures on already stretched resources, workforce capacity, and the wider community infrastructure. The ambitious, yet crucial, policy drive to shift more care out of acute hospitals and into community settings further escalates this risk, as trusts often have limited direct control over the external partners and infrastructure essential for delivering this integrated care.

Critically, trusts widely acknowledge they need to be doing something substantial in the area of transformation, but they often lack a clear blueprint or a definitive “right answer” for how to effectively approach and embed transformation at the required scale. This absence of standardised guidance and shared best practice leads to varied levels of preparedness and risks inconsistent outcomes across the New Hospital Programme, potentially undermining national objectives.

Therefore, we strongly suggest that as an integral part of its Hospital 2.0 initiative, the NHP proactively works with trusts to develop and mandate a standardised approach to transformation. This approach should be closely aligned with clear guidance on operational readiness and hospital activation. Such a programmatic framework would provide the much-needed structure, practical tools, and shared understanding necessary to manage the inherent complexities of these enormous change programmes effectively and consistently across the NHS.

Embedding transformation within capital programmes: The key stages of planning and readiness

Drawing from our interviews and work in this area, we can start to see what such a standardised process for transformation would look like. For trusts, embedding transformation requires a disciplined, iterative process, starting well in advance. This involves:

- Understanding the risk: Acknowledge the large risk carried across schemes, often due to insufficient upfront investment in transformation (headspace, resources). Failure can lead to severe operational dysfunction and financial distress. Capital investment alone cannot mitigate systemic and behavioural changes for ambitious benefits.

- Quantifying the transformation gap: Honestly assess the current versus desired future state. Rigorously define care reshaping and quantify benefits (e.g., bed reductions) through quantified interventions and moving beyond “heroic assumptions”. Comprehensive TOMs, integrating pathways, digital workflows, and workforce, are critical for defining this future state.

- Setting out a clear trajectory for filling this: A clear, actionable plan is needed, with a “preparation trajectory” starting well in advance. This must be mapped to defined projects, resources, and delivery plans. Proactive investment in TOM development, digital integration, and workforce planning is essential. Transformation progress should be balanced with formal investment milestones to avoid undermining business case assumptions.

- Delivering – and ruthlessly tracking: Robust governance is paramount for accountability. This includes active trust board involvement, oversight from programme management offices (PMOs) for driver metrics and risk management, and independent assurance (gateway reviews). Iterative approaches, continuous tracking against quantifiable benefits and, crucially, an embedded behavioural science approach are essential to drive successful implementation and sustained adoption of new ways of working.

- Having a process for escalating: Given complexity, a clear process for escalating issues, risks, and dependencies across the programme, trust, and wider system (integrated care boards, national bodies) is vital. This ensures critical challenges are identified and addressed at the appropriate level.

Implications for practice and policy

For programme leaders and trusts: Proactively integrate transformation planning from the outset of any capital programme, rather than treating it as an addition. This will require dedicating sufficient time and resources upfront to properly develop comprehensive plans. Actively engage with wider health and social care partners to ensure system-wide readiness, and foster a culture of learning by seeking out and sharing best practices from other transformation efforts across the NHS.

For the New Hospital Programme (NHP): Take a leading role in developing and mandating a clear, standardised approach to embedding transformation across all schemes. This includes providing detailed guidance and practical tools to support trusts in their planning and delivery. Furthermore, transformation readiness and progress should be formally integrated into gateway reviews, ensuring consistent oversight and accountability across the programme.

For policymakers and regulators: Consider the significant revenue implications of new builds, ensuring these are robustly factored into financial settlements for trusts. They must also ensure NHP schemes are fully integrated into broader national health and social care transformation agendas, avoiding fragmented efforts. Critically, care should be taken not to place excessive or unmanageable burdens of transformation solely on individual trusts or local systems.

For researchers: Further work is required to understand in more detail what good looks like for transformative capital programmes – examining in depth recent projects and their impact, and understanding the common themes and levers.

Conclusion

Successful healthcare capital programmes demand profound clinical, digital, and cultural transformation, not just new builds.

This paper provides a foundational understanding of the critical elements required for successful transformation. Looking ahead, our aim is to work closely with the NHP team and Wave 1 Trusts to take this work further and explore potential solutions together.

Specifically, we hope to develop and pilot a standardised approach to embedding transformation, operational readiness, and hospital activation within the NHP. By collaborating in this way, we can translate the insights from this research into practical, iterative processes. This partnership will be crucial for building national knowledge and capability in this vital area, ultimately helping the NHS to fully realise the benefits and new ways of working that these significant capital investments are designed to deliver.

About the authors

Samuel Rose is a director and Nicole Samuel a delivery director at IMPOWER.

Presenters

Organisations involved

Event news

Thinking on a new hospital – our keys for Pisa, hospital of the future

3rd November 2025

The benefits of joining up mental and physical health services

3rd November 2025

Contributing to a decade of transformation in healthcare

3rd November 2025