Optimising the design of adolescent crisis stabilisation units: An approach integrating artificial intelligence, mock-up simulations, and behavioural mapping

This paper proposes a methodology integrating physical mock-up simulations and advancements in AI for behavioural observations in adolescent crisis stabilisation units (CSUs), to help architects and stakeholders create safer, more supportive, and effective care environments.

Introduction

Physical mock-ups have been used in industry to support, evaluate and validate decision-making during the design process of healthcare environments in recent years. While existing frameworks provide guidelines for constructing physical mock-ups and conducting simulations for evaluation of healthcare environments,1 the process of building mock-ups, conducting simulations, and data collection and analysis has shown to be time-consuming and labour-intensive. Also, there has been little attempt to capitalise on recent advancements in design development and visualisation made possible through artificial intelligence (AI) in combination with physical mock-ups in healthcare design projects to optimise the process. Moreover, there is a paucity of research on innovative approaches combining physical mock-ups and AI to evaluate safety and design features for mental and behavioural health environments.2

Existing studies highlight the need for specialised spaces, such as the crisis stabilisation unit (CSU), designed for patients experiencing mental and behavioural health crises. These environments are safe, calming and therapeutic, featuring ligature-resistant fixtures to support both patient wellbeing and effective care delivery (Balfour & Carson, 2024).3 However, guidelines lack specific recommendations regarding built environment features, such as zone adjacencies, materials, furniture type and arrangement, or nursing station designs for settings accommodating adolescent patients. While built environment features, such as nursing station and patient room design in adult inpatient settings are well-studied,2,4,5 research on ambulatory behavioural health environments, such as CSUs, and their milieu environments providing care for a selected group of adolescent patients who experience mental and behavioural health crises, remains limited.

To address these gaps, an interdisciplinary team of researchers from academia and industry partners conducted a pilot research effort for designing a safe adolescent CSU milieu using a combined approach incorporating AI and full-scale physical mock-up. The study also incorporates recommendations from the EMPATH (Emergency Psychiatry Assessment, Treatment, and Healing) unit model6,7 and trauma-informed design principles to improve the environment of care and patient wellbeing.8

Methodology

Low-fidelity, full-scale physical mock-up

The construction of the physical mock-up was conducted during a four-week workshop in a lab space on a university campus in the southern United States; the steps are described in Figure 1.

Abstract

Physical mock-up simulations and behavioural mapping have been used in industry to evaluate and validate decision making during the design process of healthcare environments in recent years. The Health Quality Council of Alberta (HQCA) has published a framework for conducting simulation-based mock-up evaluations for healthcare environments ('Healthcare Facility Mock-up Evaluation Guidelines', 2020). However, there has been little attempt to leverage recent advancements in design development and visualisation made possible through artificial intelligence (AI) in combination with physical mock-up simulations to investigate behavioural patterns, improve the environment and optimise care processes for mental and behavioural health patients.

This pilot study aims to bridge the research gaps mentioned above by incorporating AI-driven tools, such as computer vision and machine learning, into physical mock-up simulations to improve safety in care environments for adolescents experiencing mental and behavioural health crises. Three scenario-based simulations (20 minutes each) were conducted and video-recorded in a full-scale physical mock-up of a crisis stabilisation unit (CSU), in collaboration with a panel of experts consisting of clinicians and behavioural practice leaders (N=5) and healthcare designers (N=13) on a university campus. Participants’ feedback on different design features in the CSU (e.g. nursing stations and furniture) was obtained following each scenario through paper-based questionnaires, the failure modes and effects analysis (FMEA) tool, and focus group discussions. The focus groups were recorded, transcribed verbatim and analysed using MAXQDA (2022). Customised computer vision algorithms will be developed to identify and extract critical event clips that highlight challenging behaviours and unsafe interactions of participants with physical environmental features, such as furniture or contraband. The frequency of the identified events will be compared against manually coded ones using the Observer XT software (version 17.0), based on a modified coding scheme for challenging behaviour developed by Delgado et al. (2017). Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations and percentages) will be used to analyse and report the data from observations, questionnaires and focus groups. All analyses are conducted using RStudio (RStudio Team, 2020).

Findings from this study will build on the existing simulation-based mock-up evaluation tools and help healthcare designers and stakeholders optimise spatial layouts, environmental features and care processes in adolescent CSUs to better support patients experiencing mental and behavioural health crises. By proposing an innovative methodology integrating physical mock-up simulations, advancements in AI and behavioral observations, this research aims to improve safety and efficiency in care environments that address the unique needs of this vulnerable population.

Learning objectives

- Develop an innovative approach integrating AI-driven tools, such as computer vision and machine learning, into physical mock-up simulations to improve safety in adolescent crisis stabilisation units

- Understand the environmental safety features in adolescent crisis stabilisation units through mock-up simulations and address the unique needs of this vulnerable population

- Validate customised computer vision algorithms by comparing their results with observations and manual coding methods

Figure 1: The process of constructing the full-scale mock-up

Figure 1: The process of constructing the full-scale mock-up

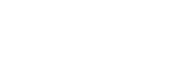

To initiate the mock-up construction phase, a base layout for the milieu environment was adapted from a real-world unit in its design phase and optimised in collaboration with industry partners based on the EmPATH unit model principles to accommodate adolescent patients experiencing mental and behavioural health crises. The unit layout was tested using floor tape prior to building the physical mock-up. The mental and behavioural furniture type and layout were determined for the mock-up through consultations with behavioural health furniture manufacturers (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: The base layout for the CSU environment

Figure 2: The base layout for the CSU environment

Two design concepts were developed for evaluation of the nursing stations in the physical mock-up, including a semi-enclosed nursing station using transparent materials (Plexiglas enclosure) for safety, privacy and confidentiality and an open nursing station design for facilitating interactions between caregivers and patients in the milieu. The design and construction of the nursing stations in the low-fidelity physical mock-up remained flexible to allow for modifications by end-users during the scenario-based simulations (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Semi-enclosed nursing station (left) and open nursing station design concepts (right) for evaluation in the physical mock-up

Figure 3: Semi-enclosed nursing station (left) and open nursing station design concepts (right) for evaluation in the physical mock-up

Scenario-based simulations

A care scenario was developed for de-escalation of an agitated patient with a high risk of harm to oneself or others in the milieu environment. The scenarios were enacted with a team of experts (n = 5) and two teams of six novice healthcare designers (n = 12). Each simulation session lasted about 20 minutes and evaluated two settings: a milieu environment with a semi-enclosed nursing station; and a milieu environment with an open nursing station.

Data collection and analysis

Noldus observation Labs was used to obtain video and audio recordings of the simulations in the CSU mock-up. Participants’ feedback regarding the unit, as well as the furniture type and layout, was collected via paper-based questionnaires following each simulation. Focus group discussions (see Figure 4) were also held following each simulation and participants’ feedback was recorded. The focus groups were recorded, transcribed verbatim, and will be analysed using MAXQDA (2022). Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, and percentages) were used to analyse and report the data from questionnaires and focus groups. All analyses will be conducted using RStudio (RStudio Team, 2020).

Figure 4: Focus groups with participants following the scenario-based simulations

Figure 4: Focus groups with participants following the scenario-based simulations

Simulation video analysis via AI

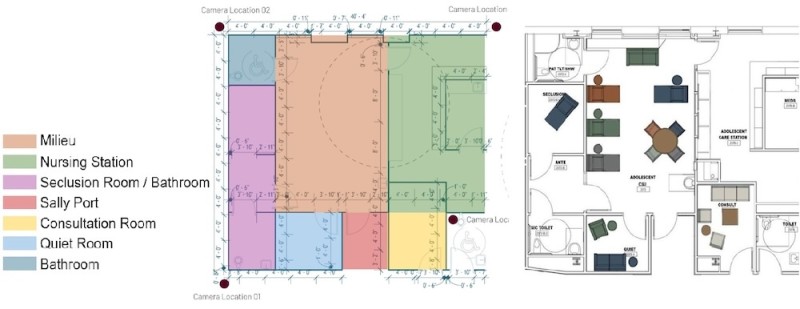

To automate behavioural mapping during physical mock-up simulations using AI, a video analysis pipeline was developed using computer vision techniques to detect, track and localise individuals throughout each scenario (see Figure 5). Each frame of the simulation videos was processed using a state-of-the-art object detection model (YOLOv12), to identify the presence and location of people in the scenes (Tian et al., 2025).9

Additionally, a tracking algorithm (Deep SORT) was employed to assign persistent identity labels to each detected person based on appearance and motion cues. Using the tracked positions and bounding boxes, we investigated the spatial relationships between participants and environmental features, such as furniture, materials, and nursing stations in the simulation videos.

Figure 5: Illustration of the floor plan and camera views of our physical mock-up

Figure 5: Illustration of the floor plan and camera views of our physical mock-up

Results

Physical mock-up simulations

Overall, 17 participants took part in the mock-up simulations, among whom 67 per cent were female and 55 per cent were in the 18-24 age range. Also, 12 participants were novice healthcare designers or educators, and five participants were experienced behavioural practice leaders (n = 3) and psychologists (n = 2). Findings from questionnaire data obtained following the scenario-based simulations indicated discrepancies in the evaluation of open versus semi-enclosed nursing stations between experts and novice designers. Experts rated the semi-enclosed nursing station higher than the open nursing station in terms of visibility (M = 4.2, SD = 0.45 versus M = 2.8, SD = 0.84) and elimination of blind spots (M = 3.9, SD = 0.89 versus M = 2.2, SD = 1.09). Also, experts rated visual and acoustic privacy slightly higher in semi-enclosed nursing stations compared with open ones (M = 3.67, SD = 0.82 versus M = 3.20, SD = 0.84). Focus groups revealed that experts identified blind spots compromising patient and staff safety in the milieu environment with open nursing station design, and proposed design strategies, such as round corners or including a charting station in the milieu to improve sightlines and visibility in the unit. On the other hand, novice healthcare designers ranked the open nursing station design slightly higher in terms of caregivers’ visibility and access to the milieu environment compared with the semi-enclosed design (M = 3.67, SD = 1.03 versus M = 3.33, SD = 0.82). They also proposed modifications to the open nursing station design by incorporating secondary doors adjacent to the station, enabling controlled access to the milieu during emergencies (see Figure 3). Additionally, participants proposed alternative placements for the seclusion zone owing to lack of visibility and accessibility for caregivers from the nursing station.

Evaluation of furniture types and layout via questionnaires indicated that both experts and novice healthcare designers unanimously evaluated features, including ligature resistance (M = 4.80, SD = 0.45 versus M = 4.64, SD = 0.50), stability (M = 5.00, SD = 0.0 versus M = 4.73, SD = 0.47), and edge safety (M = 4.60, SD = 0.89 versus M = 4.73, SD = 0.47) highly in the unit. However, based on the focus group discussions, participants described the unit’s furniture layout as cluttered, potentially hindering caregiver mobility during emergencies. When asked to select their preferred type of furniture for the milieu environment, most participants selected a seat with an ottoman followed by a behavioural health recliner to be included in the unit.

Simulation video analysis via AI

Two main tasks were analysed in this study utilising AI tools in our pilot study: participant detection and pose estimation; and key participant identification and 3D localisation in real time.

Participant detection and pose estimation

Using YOLOv12, all participants in simulation videos were annotated with bounding boxes and assigned specific identifiers, enabling consistent tracking throughout each simulation scenario (see Figure 6). Following detection, Human4D was applied to estimate the 3D body pose and shape of each participant.10 The estimated meshes were colour-coded by identity and projected back onto the original camera views to facilitate visual interpretation and downstream analysis while keeping participants anonymous in simulation videos.

Figure 6: Results of person detection and pose estimation. YOLOv12-based person detection with bounding boxes and identity tracking (on the left) and full-body pose and shape estimation using Human4D (on the right)

Figure 6: Results of person detection and pose estimation. YOLOv12-based person detection with bounding boxes and identity tracking (on the left) and full-body pose and shape estimation using Human4D (on the right)

Key participant identification and 3D localisation

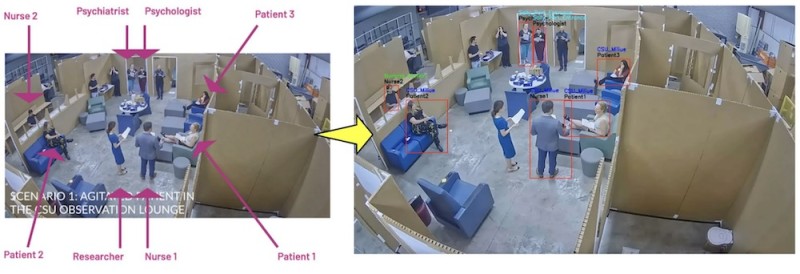

Manual annotation of key participants (e.g., nurses, patients, psychologists) in the initial frames of each scenario was conducted (see Figure 7). These labels were then used to bootstrap an automatic tracking pipeline that could consistently identify and follow each participant throughout the simulation. To automate the process, we developed a video analysis pipeline combining participant detection, tracking and re-identification. Each frame was processed using YOLOv12 to identify the presence and bounding boxes of participants in the scene. To maintain consistent identities over time, the Deep SORT tracking algorithm was used to link detections based on both motion cues and visual appearance features.

Figure 7: Qualitative results of person detection and localisation. Participant roles in physical mock-up simulation (left) and computer vision-based algorithm automatically detecting and localising key participant roles in subsequent video frames (right)

Figure 7: Qualitative results of person detection and localisation. Participant roles in physical mock-up simulation (left) and computer vision-based algorithm automatically detecting and localising key participant roles in subsequent video frames (right)

Discussion

This multi-methods pilot study investigated the design of an adolescent crisis stabilisation unit environment using full-scale, low-fidelity mock-ups and AI. The study particularly evaluated two iterations for the nursing station design in a CSU’s milieu environment accommodating adolescents experiencing mental and behavioural health crises.

The findings showed discrepancies in evaluation of open versus semi-enclosed nursing stations between experts and novice healthcare designers. While experts preferred the semi-enclosed design owing to improved visibility, lack of blind spots, and privacy in the unit layout, novice designers rated the open nursing station higher in terms of visibility and access to the milieu environment for caregivers.

Focus group discussions highlighted potential failure modes in care processes for each nursing station design and proposed strategies for optimising the space through rearranging the furniture layout and room adjacencies.

These findings are in line with reports from a study in an inpatient milieu environment, where nurses expressed concerns regarding privacy and confidentiality of communications in the open nursing station versus an enclosed one. However, the nurses stated that the open nursing station provided a better opportunity for visibility and observation of the milieu.4 On the other hand, reports from a study with a repeated cross-sectional, pre-test-to-post-test design in an adult acute care psychiatric unit showed no statistically significant differences in caregivers’ perception of the milieu environment after transitioning from an enclosed nursing station to an open nursing station design.5 It should be noted that both studies mentioned above were conducted in adult inpatient settings, and additional research is needed on nursing station design in adolescent milieu environments. While discrepancies in participants’ subjective feedback regarding nursing station designs in CSU milieus persist, AI algorithms and computer vision tools may be useful for analysing pose estimates to model behavioural states (e.g., agitation, de-escalation), quantify physical activity, and assess proximity-based risks in such settings. Nevertheless, the pilot study revealed challenges in effective incorporation of this method for real-time analysis of simulation videos.

Limitations and future work

While the video analysis pipeline contributed to detection, tracking, and re-identification of participants in real time, estimating the 3D location of participants in the layout remained a challenging and time-consuming task. Future work will build on the existing method by developing a set-up that will allow us to automatically analyse room-level occupancy, detect transitions between zones, and identify events in high-risk areas such as sally ports, seclusion rooms, or nursing stations. The set-up will also support the evaluation of spatial design by linking observed behaviours to specific regions within the environment. For instance, Figure 8 demonstrates a pilot output from four overhead cameras capturing different areas of the physical mock-up. Green lines indicate the segmentation boundaries of distinct rooms within the simulated environment. Each participant is detected using a colour-coded bounding box, with an associated room label indicating their localised position within the layout.

Figure 8: Future work related to layout segmentation and participant localisation

Figure 8: Future work related to layout segmentation and participant localisation

Conclusions and implications

Findings from this study will build on the existing simulation-based mock-up evaluation frameworks in academia and industry to help researchers, healthcare designers and stakeholders optimise spatial layouts, environmental features, and care processes in adolescent CSUs to better support patients. By proposing a methodology integrating physical mock-up simulations, advancements in AI, and behavioural observations, this study contributes to creating safer, more supportive, and more effective care environments in CSUs that address the specific needs of adolescents experiencing mental and behavioural health crises.

About the authors

Roxana Jafarifiroozabadi, PhD, EDAC is Ronald L Skaggs, FAIA endowed professor in health facilities design, and assistant professor in architecture at Texas A&M University.

Cheng Zhang, PhD is assistant professor in the Department of Computer Science & Engineering at Texas A&M University.

Stephen Parker, AIA, NOMA, NCARB, LEED AP is behavioural and mental health planner at Stantec Architecture.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Texas A&M College of Architecture for its contributions to this project. The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Health Quality Council of Alberta. (2020). Healthcare Facility Mock-up Evaluation Guidelines: Using simulation to optimize return on investment for quality and patient safety. Calgary, Alberta, Canada: Health Quality Council of Alberta. https://hqca.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Healthcare-facility-mock-up-evaluation-guidelines-FINAL.pdf

- Sachs, NA, Shepley, MM, Peditto, K, Hankinson, MT, Smith, K, Giebink, B, and Thompson, T. (2020). Evaluation of a mental and behavioral health patient room mock-up at a VA facility. HERD: Health Environments Research & Design Journal, 13(2), 46–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/193758...

- Balfour, ME, and Carson, CA. (2024). Crisis receiving and stabilization facilities. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 47(3), 511–530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2024.04.022

- Shattell, M, Bartlett, R, Beres, K, Southard, K, Bell, C, Judge, CA, and Duke, P. (2015). How patients and nurses experience an open versus an enclosed nursing station on an inpatient psychiatric unit. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 21(6), 398–405. https://doi.org/10.1177/107839...

- Southard, K, Jarrell, A, Shattell, MM, McCoy, TP, Bartlett, R, and Judge, CA. (2012). Enclosed versus open nursing stations in adult acute care psychiatric settings: Does the design affect the therapeutic milieu? Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 50(5), 28–34. https://doi.org/10.3928/027936...

- Balfour, ME, and Zeller, SL. (2023). Community-based crisis services, specialized crisis facilities, and partnerships with law enforcement. Focus, 21(1), 18–27. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.focus.20220074

- Otterson, SE, Fristad, MA, McBee-Strayer, S, Bruns, E, Chen, J, Schellhause, Z, Bridge, J, and Murphy, MA. (2021). Length of stay and readmission data for adolescents psychiatrically treated on a youth crisis stabilization unit versus a traditional inpatient unit. Evidence-based practice in child and adolescent mental health, 6(4), 484–489. https://doi.org/10.1080/237949...

- Greenwald, A, Kelly, A, Mathew, T, and Thomas, L. (2023). Trauma-informed care in the emergency department: Concepts and recommendations for integrating practices into emergency medicine. Medical Education Online, 28(1), 2178366. https://doi.org/10.1080/108729...

- Tian, Y, Ye, Q, and Doermann, D. (2025). YOLOv12: Attention-centric real-time object detectors (version 1). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV...

- Goel, S, Pavlakos, G, Rajasegaran, J, Kanazawa, A, and Malik, J. (2023). Humans in 4D: Reconstructing and Tracking Humans with Transformers (Version 3). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV...

Presenters

Event news

Thinking on a new hospital – our keys for Pisa, hospital of the future

3rd November 2025

The benefits of joining up mental and physical health services

3rd November 2025

Contributing to a decade of transformation in healthcare

3rd November 2025